Reporter Andrew Leland has always loved to read. An early love of books in childhood eventually led to a job in publishing with McSweeney’s, where Andrew edited essays and interviews, laid out articles, and was trained to take as much care with the look and feel of the words as he did with the expression of the ideas in the text. But as much as Andrew loves print, he has a condition that will eventually change his relationship to it pretty radically. He’s going blind. And this fact has made him deeply curious about how blind people experience literature.

Reporter Andrew Leland has always loved to read. An early love of books in childhood eventually led to a job in publishing with McSweeney’s, where Andrew edited essays and interviews, laid out articles, and was trained to take as much care with the look and feel of the words as he did with the expression of the ideas in the text. But as much as Andrew loves print, he has a condition that will eventually change his relationship to it pretty radically. He’s going blind. And this fact has made him deeply curious about how blind people experience literature.

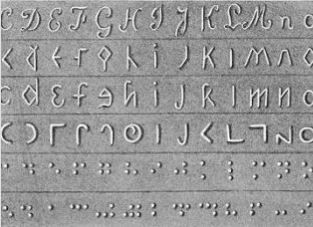

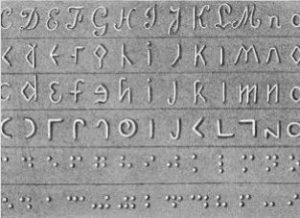

Traditionally, books are visual objects. And for centuries now, blind and sighted designers have been arguing over the most effective way to translate the visual, ink-print book into an accessible form for people without sight. For as long as blind people have been reading, there’s been this tension between systems that try to stay close to the original form of a book, and systems that radically depart from our ideas about what a book can be.